Did you know that today’s young parents were about 58% more likely to get shot at school than today’s school-aged children? Contemporary thirty-somethings actually went to schools with much more frequent shootings than today’s teenagers do.

This probably seems incorrect to most people. Most people think that nowadays kids have to deal with dangers that weren’t present in the good old days. But when you look at the data, it turns out we are all wrong about this. So why is our trusty intuition so off-the-mark?

This is Part 2 of a series on Cognitive Bias in Investing. For Part 1, see Cognitive Bias: Confirmation Bias.

How big of a risk are school shootings?

Let’s dive into the problem. How, specifically, do we “look at the data”? Being data-driven is a nice concept but oftentimes it’s not obvious where or how to start gathering and analyzing data.

In this case, we want a time series of data on school murders from a reputable source. Time series data means that we want to know how a certain statistic has evolved over time. We are looking for two key characteristics for our data:

- We want the thing we are measuring to be scaled somehow. In this case, we want school homicides per capita. In other words, we want to know how many school murders happened per thousand students per year, or something like that. We want a sense of what odds a random student had of being a victim, not the total number of attacks.

- We want a data source that uses good methods to make sure the same thing is being measured each year. In other words, there is no switch in methodology in the middle of our time series data.

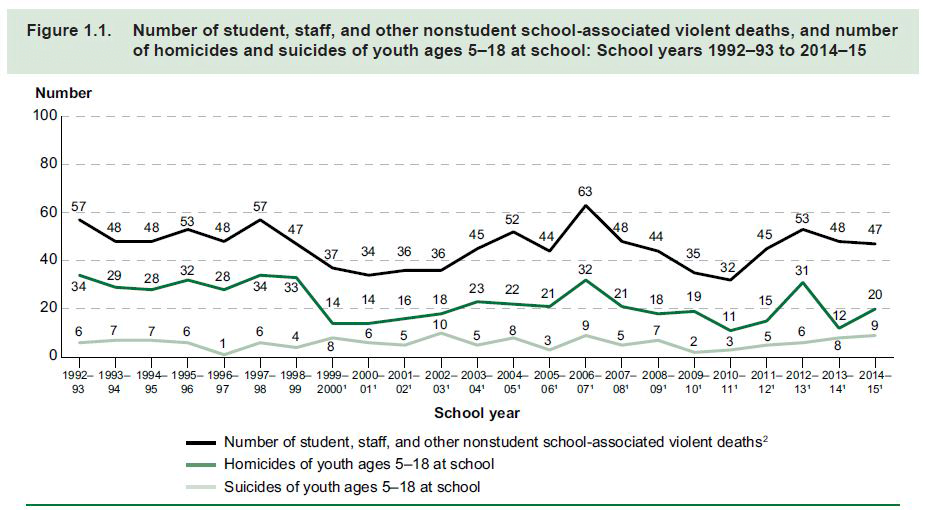

I found a good data set from the CDC that has tracked several violent crime measures in American schools since 1992 including youth homicides. I’m making an assumption here that “school homicides” is a useful proxy for “school shootings” but that’s obviously debatable. I think that my overall point stands even if there is some statistical noise about the ratio of gun to non-gun homicides over time.

You can see that although the data is a little noisy, there is a pretty remarkable shift downward that occurs around 2000. And if you compare the oldest data, 1992-1996, with the newest, 2011-2015, the average drops from 30.75 to 19.5 per year.

You might have noticed that there’s a problem with my data. We didn’t satisfy our requirement #1 above! This dataset isn’t scaled to the school-age population, it’s just the absolute number of school deaths. It seems to meet criteria #2 though, so we can try to make it work anyway. This kind of thing happens all the time in data science, and in investing. The data is never exactly what you want, and you just have to make do.

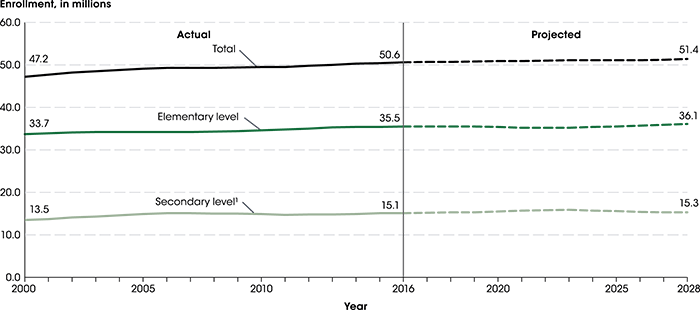

So let’s take a look at what was happening to the school-age population over the same time frame. The National Center for Education Statistics publishes the following information for American school enrollment:

Again, this data isn’t perfect. It starts at 2000 and we want it to start at 1992. But I think it’s good enough to show that over most of the time period, school attendance was stable or slightly increasing. Therefore, the large decrease we’ve seen in school homicides is, if anything, a little understated.

I did notice one more interesting detail in this dataset. The drop in school homicides occurred pretty sharply starting in the 1999-2000 school year. This was the school year immediately following Columbine. It’s possible that some of the protective measures that many schools implemented after Columbine increased school safety and that is showing up in the data. But either way, the point stands. Students in the 90s were way more likely to get killed at school than modern students.

So if the risk of a school shooting is so low, why am I worried about it so much?

This is where the concept of availability bias comes in. Availability bias is our tendency to overweight information that is the easiest to find or remember. Humans don’t always carefully analyze the full set of available data and come to a rational conclusion about what is important. Most times we just make a call based on what information is readily and easily available. This leads to a tendency to overestimate the relative importance of things that we see and hear frequently.

And information on school shootings is massively available. The concept is a terrible combination of heartbreaking, newsworthy, and politically controversial. So it’s in the news, in your face, all the time. This leads all of us to over-estimate the prevalence of school shootings. We end up over-weighting the risk of a school shooting and under-weighting more benign childhood risks like car wrecks, even though car wrecks are actually a far, far greater risk for students.

How does availability bias apply to investing?

Availability bias is all over the place in investing. We, as investors, are interested in new sectors, securities, and technologies that we learn about in the news. I personally experience this quite a bit. One of the most frequent questions I’m asked after someone learns I am a financial adviser, is “Do you think it’s the right time to put money into [insert latest investment craze].” The investment changes over time, but it’s always something that:

- is in the news all the time right now

- has recently experienced a major run-up in prices

- represents a tiny corner of the overall investment market

- has something a little goofy about it that makes it extra interesting

A few years ago it was bitcoin. Currently it’s weed and cannabinoid stocks. It’s not that these investments are bad. CBD companies are super interesting and the market really is growing very fast. It’s just that because they are so interesting, they make great TV news, and that leads casual investors to care about them way too much.

Availability bias makes us care about really small stuff

For example, the total U.S. stock market capitalization is around $30 trillion, based on the Russell 3000 total U.S. equity market index. Cannabis Market Cap lists the total cannabis stock market capitalization at $62 billion. So we’re talking about a sector representing about 0.2% of the total stock market, roughly on par with Target Corp. (TGT), the retail company at $55 billion. It would be weird if you went to a bunch of microbreweries and overheard a bunch of thirty year-old bros talking about what they think Target stock will do next month, but it’s very common to hear the same chatter about cannabis stocks.

I want to make it clear, I’m not bashing the cannabis industry in any way, I think it’s really cool and growing in a healthy way, and there are lots of really great companies in the sector. But in the total market context, the industry is just too small for the average retirement investor to spend any time thinking about.

OK so I know about availability bias. How can I improve my investing?

You can take my advice and simply ignore all financial news! The less financial and market news you expose yourself to, the less skew you will introduce into your perception of what’s important.

I write a financial advice blog. Every other week I post a list of cool financial articles that I found interesting. But you’ll notice most of them aren’t really “news”. The list is usually made up of economic macro ideas that aren’t really timely in any way. In other words, you could read a random week’s list and not miss a thing. I follow my own advice here, and try not to follow the daily market fluctuations too much.

Also, try ignoring “common sense”, at least occasionally. If you treat a problem with humility and approach it assuming you need to learn everything, you might find something that contradicts what you think you already knew. And this will help you to avoid ignoring the huge, slightly more boring parts of the market that actually matter more to your portfolio returns.

Discover more from Luther Wealth

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.